2025 panorama: Theme in focus

The Buzz – Sound in film

Sound is flowing through Clermont: In 2025, cinema is getting ready to be heard. This retrospective invites you to rediscover cinema through the prism of sound, a universe in which each murmur becomes a vital actor of the plot.

Though born silent, film has always been animated by sound. From its very beginnings, pioneers such as Léon Gaumont sought to synchronize images with sound. Dolby Atmos, DTS: X, Auro 3D… Today, even if sound only represents a small portion of production costs, it has become essential to the cinematic experience. As Alfred Hitchcock once said, “Sound is 50% of the image.” This retrospective pays homage to the creators of these auditory universes, to the artists who capture and transform sounds in order to create a cinematic language.

We invite you, through these four programs, to discover films in which each sound tells a story, where each vibration amplifies an emotion. Foley artists, boom operators, sound engineers and field recordists create atmospheres that surround the onscreen image, transforming sound into its own narrative component.

Sound effects: behind the scenes

The world of cinema often starts in studios, with silence giving way to the magic of foley artists. In The Secret World of Foley (England, 2014 – photo 1), like a magician revealing his tricks, we discover the behind-the-scenes world of sound effect creation. Foley artists recreate the sounds of a film set in a fishing village, where each step on the pebble beach, each and every movement is music of its own. This invisible but crucial work is a detailed art that feeds the illusion of reality.

The process is even more riveting in Hacked Circuit (USA, 2014 – photo 2), in which a sequence shot portrays the sonic recreation of the final scene of Coppola’s The Conversation (USA, 1974). The sounds of the Californian street plunge us in a universe of surveillance and control, where tension rises with each sonic breath, making us witness to an omnipresent paranoia.

When sound awakens hidden emotions

Sound has the capacity to awaken hidden emotions and fears. On the Origin of Fear (Indonesia, 2016, Lab Competition 2017 – photo 3), is a striking example of this. Set in a suffocating atmosphere, a voice actor, isolated in a studio, lends his voice to characters with a violent past. While the director remains invisible, sounds and voices are charged with embodying terror, transforming the studio space into a haunted site where fear becomes tangible.

This exploration of the invisible also resonates in La Peur, petit chasseur (Fear, Little Hunter) (France, 2004, National Grand Prize 2005 – photo 4) of the late Laurent Achard. Here, sound becomes its own full-fledged character. In a nine-minute static shot, a house appears to be calm, but the surrounding sounds tell a whole different story, creating an invisible, almost palpable, tension. The film demonstrates the power of off-camera shooting, or how sound can conjure the invisible and allow a silent anguish to rise the surface.

A different way to hear the world

Sound can also reveal inner experiences, transforming our relationship to the world and to ourselves. Two powerful films adhere to this notion, Notes on Blindness (England, 2016, Lab Competition 2014 – photo 5) and O Menino que Morava no Som (The Boy Who Lived In The Sound) (Brazil, 2022 – photo 6).

Notes on Blindness follows theologian John Hull, who has become blind, through a sonic journal that captures his experience of blindness. Every sound becomes an essential sensory landmark, replacing sight and creating a unique universe in which the absence of image reinforces the intensity of sounds. The viewer is invited to “see” with their ears, and to feel the invisible world with unprecedented intensity.

In O Menino que Morava no Som by Felipe Soares, we follow Timba, a deaf young man who comes from a Brazilian suburb. Isolated from the lack of contact with Brazilian Sign Language, Timba must navigate the frustration of being unable to communicate his desire for interaction. His situation is made worse by a society that isn’t always accepting of deafness, with some families opting for cochlear implants. This film paints a sensitive portrait of the social and personal barriers that Timba faces, all while revealing the force and the complexity of the sonic universe in which he evolves. Between the silences and the amplified sounds of everyday life, we discover a world of emotions unsaid, where communication is just as much a struggle as it is a desire.

Another film, Di Shi San Ye (Thirteenth Night) (China, 2023, Lab Competition 2024 – photo 7) by Rachel Xiaowen Song, explores the disturbing impact a mysterious telephone call has on the life of Xiaoxue, a grieving young woman. After receiving a phone call from her late fiancé, she finds herself confronted with paranormal forces that throw her existence into disarray. With its blend of psychological suspense and paranormal elements, the film plunges us into a deep sensory exploration, where sound and noise create an atmosphere of discomfort and uncertainty, reinforcing the feeling of loss and distortion of reality.

When sound changes our perception of daily life

In En Cordée (France, 2016, Award for Best Original Score 2017 – photo 8), by Matthieu Vigneau, sound detaches itself from image, generating a subtle discordance. Through an out-of-sync voice-over on images of a hike, the film establishes a dissonance that disturbs our perception and creates a discrete but striking tension. Everyday life, though familiar, becomes strange, reminding us that sound has the power to change reality.

Some films push the limits even further, transforming sound into a full sensorial experience. Plot Point (Belgium, 2007, Lab Special Jury Prize 2008 – photo 9) by Nicolas Provost, for example, immerses us in the nighttime streets of New York, where life is amplified by desynchronized sounds and oppressing music. Times Square becomes a space that is fascinating and disturbing all at once, where sound distorts our perception of reality.

Nature itself becomes an open-air orchestra in Polyfonatura (Norway, 2019 – photo 10) by Jon Vatne, where each natural sound becomes a note of a symphony, offering an immersive experience in which sonic art blends with the natural environment.

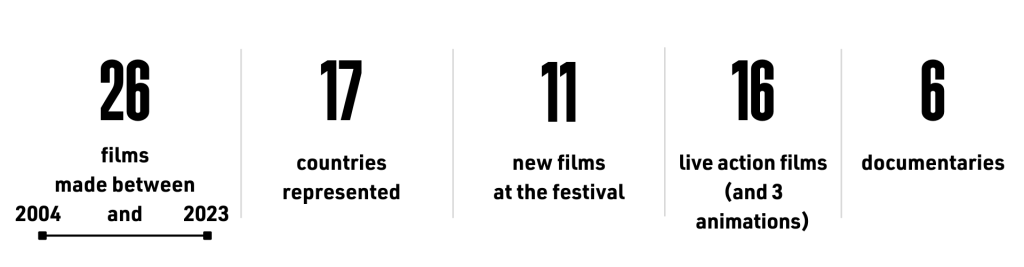

With 26 films from 17 countries, this retrospective invites you to rediscover cinema through the prism of sound. These creators, often invisible, transform each murmur of everyday life into a work of auditory art, offering an experience in which sound is the unseen hero, and where your ears become the guides to an unparalleled cinematic journey.