Lunch with Gramercy

Interview with Jamil McGinnis and Pat Heywood, codirectors of Gramercy

Can you explain the title?

Jamil: The world of Gramercy existed before we were exposed to it. It’s a self-proclaimed name of an area of Piscataway that this group of guys signified as a homage to a kinship they had formed over the years. Originally, Mook, one of Shaq’s friends that is in the walk up of the movie, lived on Gramercy Drive where they used to throw parties in the basement of his house. It became an area and now a fabric of their own identities. It was only right to keep the name true to what has been formed over the years. The old English definition of the word translates to “many thanks.” If anything, we kind of like the title of the film to be a thank you to the guys for exposing us to their world and ultimately, letting the world in on their beautiful, tight-knit brotherhood.

How much were you interested in the question of grief and do you plan to deal with this subject in further films?

Pat: This unanswerable question was the bedrock of the language we sought to create. Not what happened, or where, or when, or how… those answers don’t change much. So, rather than focusing on plot, we wanted to explore this subjective experience, the present-tense state of being. What does it feel like to live with grief and depression? That was everything. We tried to inhabit Shaq’s internal life in glimpses with these different worlds. They exist without rationality. It’s a soul splitting, between the inner essence of suffering that can’t be named and the material reality around you. When you’re grieving, or living in a depressive state, you are so inward. The pain feels more real than anything around you, but you eat, you walk, you see your friends. You put on a mask, push the pain away, unable to recognize the sorrow, but it doesn’t leave… it appears beyond control. We tried to drift between these two spaces, yet in the end, find a harmony: it’s all you. It’s always all you. It’s one big mirror. I am certain there will be further exploration in future films. I’m not sure what it will look like, but it will be there. It’s been such an integral part of who I am, who we are, that to not push on that door more would be an act of avoidance. Loss is all around us, always. Some losses we feel greater than others, but it’s truly the one thing we can all be certain of. The journey is to explore the beauty and the pain of the truth that everything changes and nothing lasts.

How did you work on the characters’ accents and phrases, and why?

Jamil: That’s all them. There is no direction from Pat and I on that. Our process is surrounded on the ideal of finding ourselves through our characters that already exist in the world. After spending time with them over the years and engraining ourselves in their world, we were able to understand their lingo, cadence and how each one of them communicates with one another. The script we wrote that was inspired from their characteristics, became a blueprint for the guys to feel comfortable and react in a world that they know all too well. We were there to capture those moments. All the attributes that make this a “New Jersey” centric film was merely us staying true to the culture and the realities of the guys themselves as opposed to having to recreate it. The cast is cut from that New Jersey cloth and that beautifully shines through.

Do you often work on body language and expression dance or did you choose this approach for this film especially?

Pat: Both, I think. It was important with Gramercy in particular because dancing is an integral part of the New Jersey culture. The music, the movements, the energy – it’s all Jersey club. Those guys have been dancing together like that since they were young. For us, it was about letting that shine. Creating an environment where it had space to breathe. There’s something about dancing that gets at the truth of what we are. This connection of mind and body that can’t be rationalized or narrativized… Presence that exists beyond language. When we first see dance in the film, it’s observed objectively as a performance. We see it again shortly, and it’s this dissociative fugue state, the body running from the mind. Toward the end, we finally see Shaq dance, and it’s a transcendent moment of discovery… being alive, being you, as a state of pure presence, as opposed to a person trying to push something away. It’s a unification of the self.

Why did you choose black and white for the main part of the film?

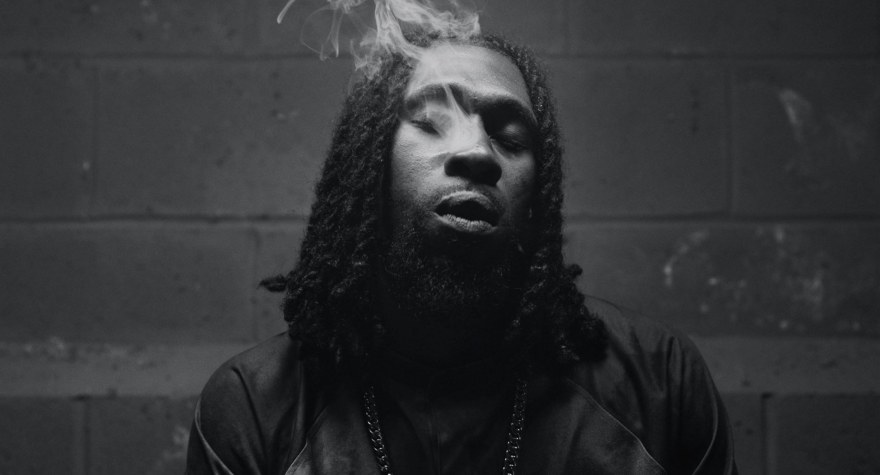

Jamil: Black and white has this interesting attribute in cinema of communicating “something of the past” given it was the first form of image-making before color. And usually juxtaposed with color, it takes on the element of surrealism or otherworldliness. The inherent trait it holds is the instant refocusing of the world around us, since color is a part of that natural world that we think we understand. The absence of color makes you focus on what’s objectivity in frame opposed to being mesmerized by the richness of something on face-value, or again, being mesmerized by the world we think we know. To see the world without an attribute we all know to be true, it begins to help ask questions of what is real, what is not, when in actuality, everything within these 22 minutes of the film is the reality for our main character. Letting black & white be our everydayness caused for the concept of refocusing the idea of standardized methods in cinema to convey realities. Not everyone’s reality happens to be the same so there is never just one method to use in order to communicate something. At the time of our color grade, the feeling black and white gave me communicated the truth of how I was viewing the world at that moment. Very objective, with no lush fascination of life’s vibrancy. Once we both made that decision, we realized this was the decision that was needed to be made all along. It was meant for us to find it when we did. It was more so a reflection of us which ultimately mirrored the reflection of our main character.

If we were to go back into lockdown, what cultural delights would you recommend to alleviate our boredom?

Jamil: I continue to always revisit Nazim Hikmet’s work, specifically Human Landscapes of My Country so I think this is a must to read. That book is the blueprint to how my mind works and how I begin to view everything I’m interested in. His words strip the human back to the core principles of enduring, love, and more importantly, how each person goes about doing that. Him being a political prisoner in Turkey for 12 years when writing this book, he crafted his reality in this surreal, non-linear way that I think resembles life closely, more than anything I’ve read before. We’ve been in the world, trying to isolate for a couple of months for the sake of humanity while he and many others have been forced to isolate for years on end. Nazim jumped between what reality is versus the story we paint around our realities. That can either hurt you or help you endure. I’ve been reading a lot of Frantz Fanon and just started The Rebel by Albert Camus. I’m fascinated to look at different perspectives of human struggle and realized everyone is trying to reach some universal internal peace. So I ask, with each person’s relative realities in mind, who’s to judge anyone based on the method in which they wish to seek their personal truths? I’d say visit lots of Abbas Kiarostami, Andrei Tarkovsky, Shirin Neshat. The foundation of their works has shifted the way I internalize the world. With care and mysticism. Abbas is the filmmaker I look up to in both cinema and my view of the world. Find some of his early works before the Koker Trilogy like The Traveler and Homework. I think by seeing those films, I was able to see someone’s voice changes pitch over the years but still coming from the same soul.

Pat: I recently watched a Chinese film from a few years ago called An Elephant Sitting Still. That was incredible. It’s very sad, and a bit of an endurance test, but for folks who don’t mind challenging cinema, it’s worth four hours of your life. I’ve been watching a lot of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Taiwanese films from the ’80s and ’90s. That island produced some titans… Hou Hsiao-hsien, Tsai Ming Liang, Edward Yang. Yi Yi is one of the best films ever made. It takes your breath away with its humanity. I’ve also been listening to a lot of popular music from the ’60s and ’70s. Lots of Jimi Hendrix, Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, Beatles, Bob Dylan, Talking Heads. Full records, beginning to end… I like to lay on the floor, but I get up and dance when compelled. I used to listen to music passively when I was doing something else, but it’s been a soulful use of energy to give myself over to it. I close my eyes, it feels a bit like I’m leaving my body, traveling through time.