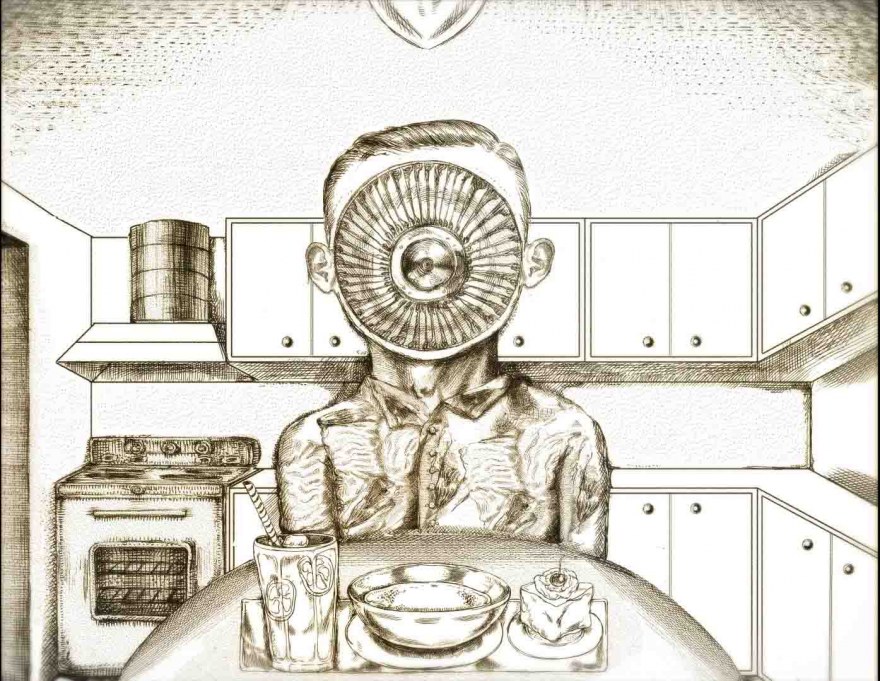

Night cap with Turbine

An interview with Alex Boya, director of Turbine

Would it be correct to see an analogy with the current impact on the way new technology has immersed itself in our lives to the detriment of the way we connect as people?

Yes, the way technology has settled into our lives has changed us. However, I don’t know if it’s to the detriment of the way in which we interact with each other. In my film there’s a resistance to technology but, little by little, it seeps into the house in the form of banal devices then exerts a subliminal domination to the point where these household appliances become an extension of our bodies. Turbine is set in the 1940s at the time when technology entered the domestic space with great fanfare thanks to the first household appliances. The story portrays the turbine as a symbol of modernity and of the worship of technology that has redefined society. Ours is no exception because smart phones, watches and other gadgets have invited themselves shamelessly into our daily surroundings and make us, we could say, lose face. Instead of focusing on contemporary devices such as smart phones and the Internet, I wanted to go further back in the past to look at how the war contributed to the development of these technologies.

What made you think of specific engines, a war plane? A locomotive?

The origins of Turbine, curiously, don’t stem from a personal experience but a dream. I had a dream about a big field and a man standing with his back towards me. When I got close enough to see his profile, I realized his face was flat. When I was standing in front of him, I saw a turbine in a hole in his face and he was drooling a sort of saliva/motor oil. The man asked me to come closer so he could whisper something in my ear. I understood everything his steady, mechanical voice uttered. Once I woke up, I realized that it was simply the noise from the air conditioner in the bedroom.

Tell us a bit more about your style of animation. I felt there was an air of etchings/drawings like those found in old 19thcentury archives…

I was a medical illustrator for McGill University and for other clients in Montreal. I like doing this type of drawing because that’s how I perceive the body. The task consists of creating opaque physical representations that are “matters of the soul” such as the love that unites the couple in the film; this led to the creation of a series of subdued images that make up the short film. The problems in Turbine are described and resolved like surgical operations on the body. So, I used a style that is close to the copper etching technique that reminds us of the neutral approach in Denis Diderot’s encyclopedias. It’s what I call “medical expressionism.”

Would you say that the short film format has given you any particular freedom?

The short film format gives you the possibility to be explosive. You’re not overwhelmed by the length. My freedom comes in large part from the National Film Board of Canada, NFB, one of the world’s biggest short-film laboratories where we practice the art of exploring and of expressing ourselves. It’s important to know that my family emigrated from Bulgaria to Quebec when I was two. This comedy presents two worlds on opposite extremes: my homeland – I was inspired by letters, objects and old photos dating from the period just before I was born – and my typical North American childhood during which the closest thing that resembled a conflict were battles with Star Wars figurines. At the NFB I could dig through this duality and I had the opportunity to work in the same hallway as Theodore Ushev who encouraged me to define my own rules as a writer.