Black Humor

Black Humor

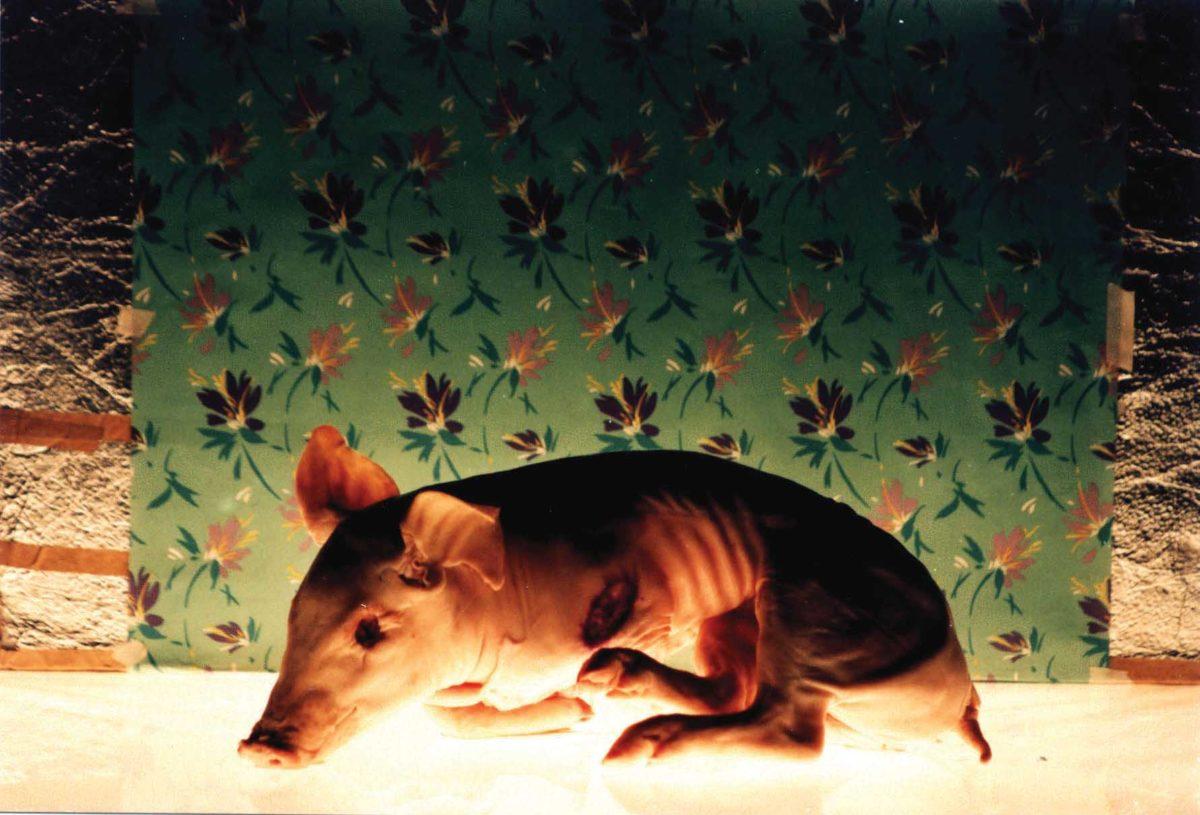

(L’union fait la force – Hanne Phlypo – 2006)

The closer we look at black humor, the more it seems to resemble humor in general. In his Anthology of Black Humor, which was banned in 1940, André Breton more often speaks of just humor, without adorning it in that color whose association he so cherished (black magic, black light…). The aphorism of surrealistic Belgian poet Achille Chavée, which exists within our collective memory, is noteworthy in this regard. He wrote, “Black humor is the politeness of despair.” However, the black has faded away after having sufficiently tainted humor to be able to afford this discretion. And when we think of German writer Otto-Julius Bierbaum, who wrote in 1909 shortly before his death, “Humor is when you laugh anyway”, we can’t help but think that this phrase would make a wonderful inscription on the frontispiece of the temple of black humor.

(Daheim – Kai Wido Meyer – 2015)

Let’s come back to Breton: in 1935 in Prague, two years before giving a conference in Paris entitled “Of Black Humor”, he defined humor as “a superior revolt of the spirit”. Echoing this in 1968, Annie Le Brun saw in black humor “an expression of victorious subjectivity”. Revolt? Now we’re getting there! If it is indeed the Grim Reaper who preoccupies us, it is this final partner that humor confronts, without irony, but with a liberating and somewhat dandy distance, a sovereign detachment in the face of the inevitable… Breton liked Freud’s joke about a condemned man being led to the gallows on a Monday who shouts, “What a great start to the week!” In fact, it is important to note that in English, black humor is also sometimes referred to as “gallows humor”.

(Pommes frites – Balder Westein – 2013)

It is important that we remember, with Elwyn Brooks White, that explaining humor is like dissecting a frog: we learn a lot from the experience, but at the end of the day, the frog is dead. So let us joyously taunt death throughout this retrospective, seated on our couch, defying it to surprise us (Blue Sofa, co-directed and interpreted by Pippo Delbono), trying to provoke it to bring back a bit of life (Daheim), or singing at the tops of our voices (L’Union fait la force). The family circle will be very present: Victor, by François Ozon (discovered in Clermont in 1994), lives in a family in decay, to say the least. Didier is on a quest to reconcile with his father on the day Marc Dutroux escapes (Travellinckx, by Bouli Lanners), Raul and his family who have some rather strange stories to tell (Interior. Familia.), young Calvin who rejoices a bit too quickly at the promise of a trip (Je vais à Disneyland).

(Blue sofa – Pippo Delbono – 2009)

We will have the pleasure of welcoming back the very British 23rd Earl of Leete who will offer us a look at his heritage (A Sense of History by Mike Leigh, winner of the Audience Award in 1993 in Clermont); Roman Polanski in his first, and rarely screened, French film (The Fat and the Lean, 1960); Michel Piccoli as the quirky commissioner in Du crime considéré comme un des beaux-arts, Grand Prix in Clermont in 1982 — and a nod to Thomas de Quincey, one of the tutelary figures of black humor.

(A Sense of History – Mike Leigh – 1993)

We will also get a feel for what Dominique Noguez calls “red humor”, or a black humor that is less existential, but more political: Ilha das Flores (Isle of Flowers) by the Brazilian Jorge Furtado left a lasting impression on all those who discovered it in Clermont in 1991. Dead Times (1965), directed by René Laloux and Roland Topor and based on a text by Jacques Sternberg, is a prefiguration that could be considered as sharing a certain kinship with the ever poignant film Des majorettes dans l’espace (1997 Clermont Audience Award).

(Ilha das Flores (L’île aux fleurs) – Jorge Furtado – 1991)

It would have been in questionable taste to dedicate this quick tour of the world (over 10 countries visited, from South Korea to Norway) to humorist Fernand Raynaud, whose last vision was that of a cemetery wall before crashing into it with his Rolls Royce. So, we are dedicating this instead to two Clermont writers: the great Chamfort (“Learn to die! And why? We do it very well the first time around.”) and Maurice Roche, who received the 1987 Grand Prix of Black Humor for the novel Je ne vais pas bien mais il faut que j’y aille. As black as lava rock over time…

(The Obvious Child – Stephen Irwin – 2013)