Lunch with Peripheria

Interview with David Coquard-Dassault, director of Peripheria

In what way are you connected to the suburbs you describe in Peripheria? How did you decide where to shoot? Do your shots truly exist somewhere, or are they a product of your imagination?

Peripheria is not a real city, it’s my imagined vision of a “commuter town”. It’s a film project – looking at the traces of life in the folds of that urban world and sketching a portrait of it. The sources for this particular city are in the buildings erected in the second half of the 20th Century that shoot up out of the ground behind the thrust of the “modern movement” in urban planning and construction: Clichy-sous-Bois, Sarcelles, Marseille, or even Grenoble, where I’m from…

We created a composite world based on the photos we took while location scouting in the Parisian “banlieues“, and on archival images, radical plans like Pierre Székely’s all-concrete playgrounds, and imaginary places too. This was a conscious decision on our part, which arose from our fundamental principle of establishing a certain legitimacy, as the crises in the French banlieues keep coming back, like booster shots.

How did you create the animation in the film? Did you work from live shots?

The animators carefully watched dogs through living models and video footage, but each movement was created, or acted, as it were.

When we started, the dogs were meant to be drawn and animated using traditional techniques, but it was too hard to stick to the model, and we wouldn’t have had enough time, so we used 3D models. The animation was still created entirely by hand, though, without any software programs, the same way as in films that use figures in stop-motion. It’s a hybrid technique that lends a slightly mechanical feel, but that’s still very real. Reality gains an extra dimension through the prism of traditional animation, which highlights movement by isolating it. The effort it requires to pull this off, and the exactness of the acting, intensify the emotional charge.

The soundtrack to the film feels very precisely constructed. How did you imagine its narrative thread and how did you create your sound textures?

The film is a visual and sound journey: sound and image are linked in a delicate balance. The first thing the music does is give a thrust to the project, and we came up with a melodic framework as we were writing, with precise references to define the atmosphere and find a tempo: Geinoh Yamashirogumi’s compositions, especially for the film Akira, “Trivium” by Arvo Pärt, who is a constant source of inspiration, Jonny Greenwood’s “Bodysong”…

Since the council estate has become a primitive world, it was important to imagine the music as an expressive, tribal melody. That obviously meant pushing the percussion to the fore: drums and idiophones vibrate within the estate, resonating and reverberating to create a sort of sound topography and highlight the dogs’ movements. In counterpoint, the organ heightens the idea of a “temple” and directly echoes the tower block structure through its tall, vertical, imposing architecture.

As for the noises, besides the tonalities proper to each scene, each dog that was given its own sound image represented a considerable amount of work – bespoke sound, as it were.

Why did you want the dogs to be heard? How did you script the human beings, and what effect were you going for by showing their absence?

Through the dogs, man lies at the center of the project. Their origins came about as we wrote – they gradually became the only actors in the film, but we intended them to be subject to interpretation. There’s nothing that truly distinguishes them from the animals, but their elegant, black silhouettes and their “birth” from within the ashes make them rather like mythological creatures.

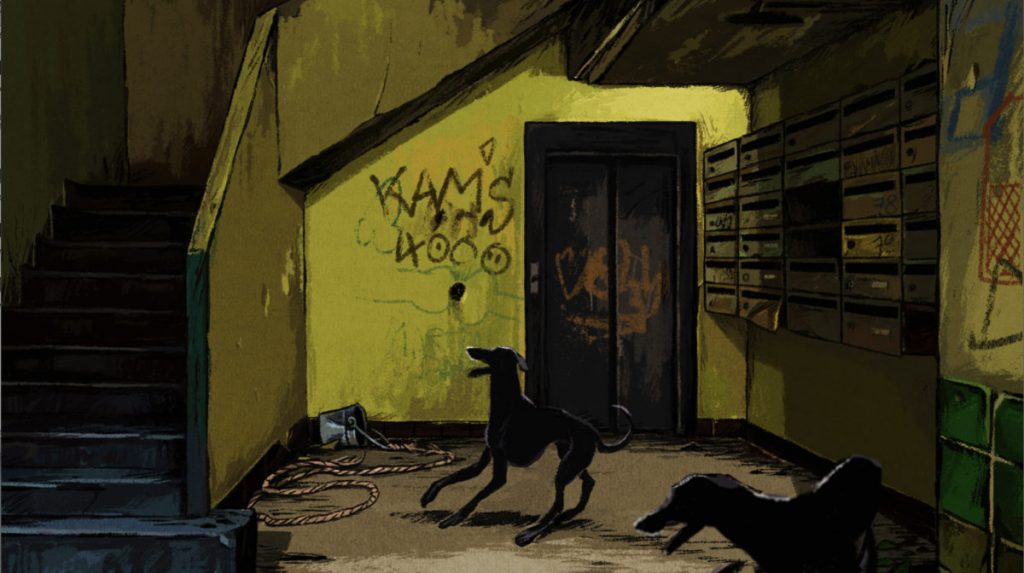

The pack enters the abandoned building like it was a modern Pompeii; it leads us through the remains of a vanished civilization. As the story develops, these surroundings act on the pack and divide it. It brings out individual personalities, it attracts some dogs and leads to their destruction, it quickly divides the group in two. Other dogs will fight tooth and nail for their territory… It’s a return to a savage world.

On the way, sound memories spring up, moments of life that had once been common in the estate. We gradually realized that those animals, in addition to finding the traces of the human beings among the deserted buildings, literally incarnated those destinies. They are a vector, a sort of materialization of the memories that fill these places… All of the film’s action revolves around that.

Why did you decide to use static shots which give a sense of immobility?

What drives the film is a conscious visual decision inspired by contemporary German photography, the movement called New Objectivity and its rigorous images of urban structures; but also by the vestiges of industrial and real estate architecture that have become “anonymous sculptures”, which share a total lack of subjectivity.

The frontality of the shots echoes the starkness of the building, the systematic layout of the façades. The shot is divided by the architectural structures; the image delimits the visible space and the framing contains the dogs just as everlasting concrete constrains the bodies. While this visual approach reinforces the feeling of constraint, it also allows us to tie together the details and create continuity among the shots.

Did you imagine Peripheria the way it is, or did you consider it a part of a larger whole, with a “before” and an “after”?

The film’s subject matter makes it a watershed moment: it sits between the ancient and modern worlds, it’s a passage between the two, like a sort of purgatory. So there are already a before and an after, but we don’t develop those ideas.

I don’t try to tie my films together, but each new project develops out of the preceding one. It’s sort of a continuation of my first film, L’ondée, which imagines a large city beneath the rain where urbanism is very evident. There are some strong similarities between the two, especially the close connection between man and his surroundings, and the idea of an urban portrait where the human presence lies just below the surface.

Does the question of street urchins interest you, and what differentiates an urchin on the street from an urchin in a council estate?

Peripheria depicts a social and geographic shift. We’re all influenced by the environment we grew up and lived in, and the experience of living with 4,000 other people in a tower block is significantly different from living in the street, which is still a means of escape for young people in the banlieues. What they have in common is that they’re both places where the dregs of modern society try to get by, where people can only count on themselves.

.

.

Could you have made the same film in another setting: the countryside, a corporation, a factory, a hospital…?

The message would be different. Today, housing estates have become historical objects, utopias where several generations of families have lived one after the other. Cosmopolitan, multicultural, multi-religious towers of Babel that crystalize the fears and tensions at a time when rejection of the other is more current than ever. It’s a very strong symbol for the modern world.

Do you think short films are effective in questioning the meaning of “environmental” units and of “macro” social units?

Any means are good. Every artistic project, whether in film or other media, aims to size up today’s world, to investigate or question. That is its mission. Animation allows you to shift your gaze, it’s a truly amazing medium. In cinema, animated feature films tend to flounder in their cookie-cutter clichés; technique has become a genre, a disembodied object. Given their meager financial stakes, short films are still an open space where you can address any topic sincerely and honestly.

Peripheria was either produced, co-produced or self-financed with French funds. Did you write the film with this “French” aspect in mind: making movie references, building a specific context (in a particular region, for example) or inserting characteristically French notions?

The impetus behind the film were the riots in the council estates in October 2005, when France was embroiled in a national crisis. So in that sense, it is intrinsically French. But the film doesn’t deal with the country’s historical, social or economic dimensions; it only looks at the walls of the housing projects. Corbusier’s followers built tower blocks in every corner of Europe, some far more impressive than the ones in France. In fact, the film’s main architectural reference comes from Italy – the Corviale structure, called the “great snake”, stretches across one kilometer, which makes it the longest housing structure in the world and prevents the Mediterranean wind from reaching the capitol. When we were in Pompeii we later found out that wandering dogs have also taken over the ruins… Peripheria‘s subject is universal.

.

Peripheria is being shown in National Competition F1.