[Editorial] A 2018 prolific National Competition

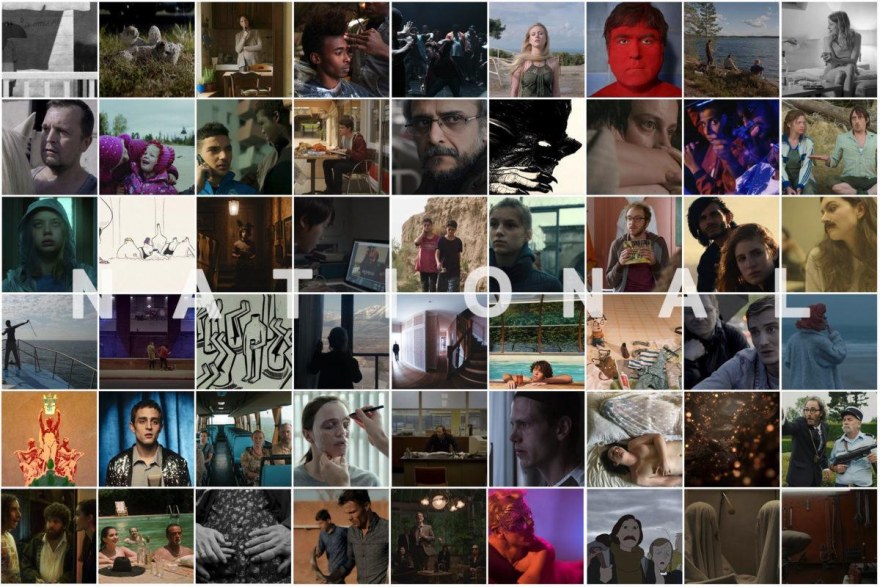

The national competition was the Clermont-Ferrand Short Film Festival’s original competition, and this year’s fortieth installment offers fifty-four films. And even though directors and producers don’t sit down and agree to follow a particular movement, making it difficult to establish trends, we can still see some general directions.

French short films are becoming more international

There are numerous factors that account for a national selection that has opened up to the world. For one, there is the French system of short film production that is the envy of the world, and initiatives such as Clermont-Ferrand’s Euro Connection encourage European and international co-productions. But French producers of shorts, as of feature films, also pay close attention to international filmmakers. Moreover, French film schools are open to foreign directors. This trend has resulted in the presence of thirteen international co-productions, nine of which are with European countries, with the others including Iran, Lebanon and Turkey. While these numbers are proof of the willingness of producers to bring in other countries, they also indicate a willingness to welcome these directors to our country in order to enrich our cinematic soil through new inspirations and know-how. We need only think of Israeli Mor, the Israeli animator who settled in France after a course at La Poudrière, or Xiao Baer, a Chinese student at La Fémis, Ru Kuwahata, a Japanese director who made her film with the American filmmaker Max Porter, or Yagiz Onur, a Turkish director who shot her film in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region.

French short films are firmly anchored in reality

Be they documentaries or fictional films that are deeply embedded in reality, French short films are tackling society and the world head on.

Emilien Cancet and Gustavo Almenara offer us three testimonials from the Calais Jungle, gathered in the midst of a session at The Barber Shop, where modesty and memories intertwine. In Boomerang, David Bouttin we follow a man as he strives to find a job and feel his anguish in the face of the absurdity of his condition. In Bye bye les puceaux, Pierre Boulanger humorously and tenderly depicts the wanderings of two teenagers from the projects whose romantic interests go against the established and enforced dogmas of their peers. Next we head to Mexico in Clarisse Hahn’s Mescaline, where we meet a couple of tourists who started off wanting to follow in the footsteps of Carlos Castenada and Antonin Artaud in search of peyote, the cactus known for its psychotropic and hallucinogenic properties. Instead their journeys end up hopelessly disrupting the balance of a village family. Laura Haby’s My Eyes Are Gone plunges us into the intimacy of a brilliantly directed poignant and tragic story. Jean-Charles Paugam offers to take us on a risky look at a world that is further from politics than practical considerations in Nuit debout. Adrien Lecouturier and Emma Benestan’s Un monde sans bêtes takes us to the Camargue where we meet a teenager who is about to embark upon his first job and an apprenticeship to life beside his strict uncle, who has an almond plantation and whom he admires. Ursinho, a film by Stéphane Olijnyk, leads us into the depths of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas through an incredible social and sensual parable that directly confronts several taboos of Brazilian society, including racism, homosexuality and social violence. The director Edzard Rolan sets off in search of his actor, who had vanished after converting to Islam, and, without ever passing judgement, invites us on his journey and his reunion. At the same time, in the background we clearly see what fantasies and questions this type of transformation can give rise to in the current climate. And finally, Jules Follet’s Waterfountain literally plunges us into a bankruptcy case that turns into a nightmare for the CEO who is embroiled in problems with his accountant, his suppliers, his staff, the telephone salespeople and his water fountain.

Directors and producers are once again making genre films

It’s great news for the national selection that genre films are back in full force in Acide, Chose mentale, La naissance du monstre and Un peu après minuit, by Just Philippot, William Laboury, Zoran and Ludovic Boukherma, and Jean-Raymond Garcia and Anne-Marie Puga respectively. These four films help us to rediscover the untainted pleasure of the fantastic, the strange, horror films and detective stories, each in a very different style.

Comedy also makes a come-back

Let’s end with what is often the most difficult thing in films, making people laugh. With no fewer than twelve films, comedy makes a nice come-back in the French films we’re offering in the national competition this year.

Directors are very clearly eager to try their hand at comedy or at least to toy with lightheartedness, which also points to a dire need to laugh, to make others laugh and to make fun of things in order to get some distance. And there’s something for everyone! In addition to Bye bye les puceaux, Nuit debout and Waterfountain, we should mention Claude Le Pape’s Cajou, Aurélia Morali’s La nuit je mens, Parades by Sarah Arnold, Pourquoi j’ai écrit la Bible by Alexandre Stieger, Noé Debré’s Le septième continent and Master of the Classe by Carine May and Hakim Zouhani, all comedies with superb scripts that draw us into falsely carefree worlds. We can delight in rubbing elbows with, in no particular order: a completely neurotic but endearing father, a Tinder date that is as unlikely as it is touching, a libertarian and a representative of order who were never meant to meet, a son who cannot handle being overshadowed by his eccentric father’s behavior and decides to meet Jesus Christ, an investigator deep in a metaphysical crisis shuttling between the financial world and ecological destiny and a substitute teacher on the verge of a nervous breakdown who is beset by numerous difficulties.

The national selection also offers some deliciously burlesque comedies, such as François Bierry’s Franco-Belgian production Vitah, a film that shows us the joys and sorrows of business conferences where the goal is to remotivate one’s employees by putting them in unusual situations. Similarly, Antonin Peretjatko’s Panique au sénat could easily be described as the improbable meeting of the Philippe de Broca’s cinema and the Nouvelle Vague. Peretjatko has come back to making short films after the commercial success of his feature films, proving once again that this format is not simply a stepping stone towards features, but involves its own risks and through its freedom offers incredible possibilities for daring that we will continue to defend for the next forty years at least!